REPORT HOME > staying on line

October 2024 | technology report | SPACE

The extent to which frontline military personnel on the ground depend on space-based systems for vital connectivity and intelligence is often underestimated. Shephard examines what the latest generation of satellite constellations can provide and the need to secure them against jamming and even kinetic threats.

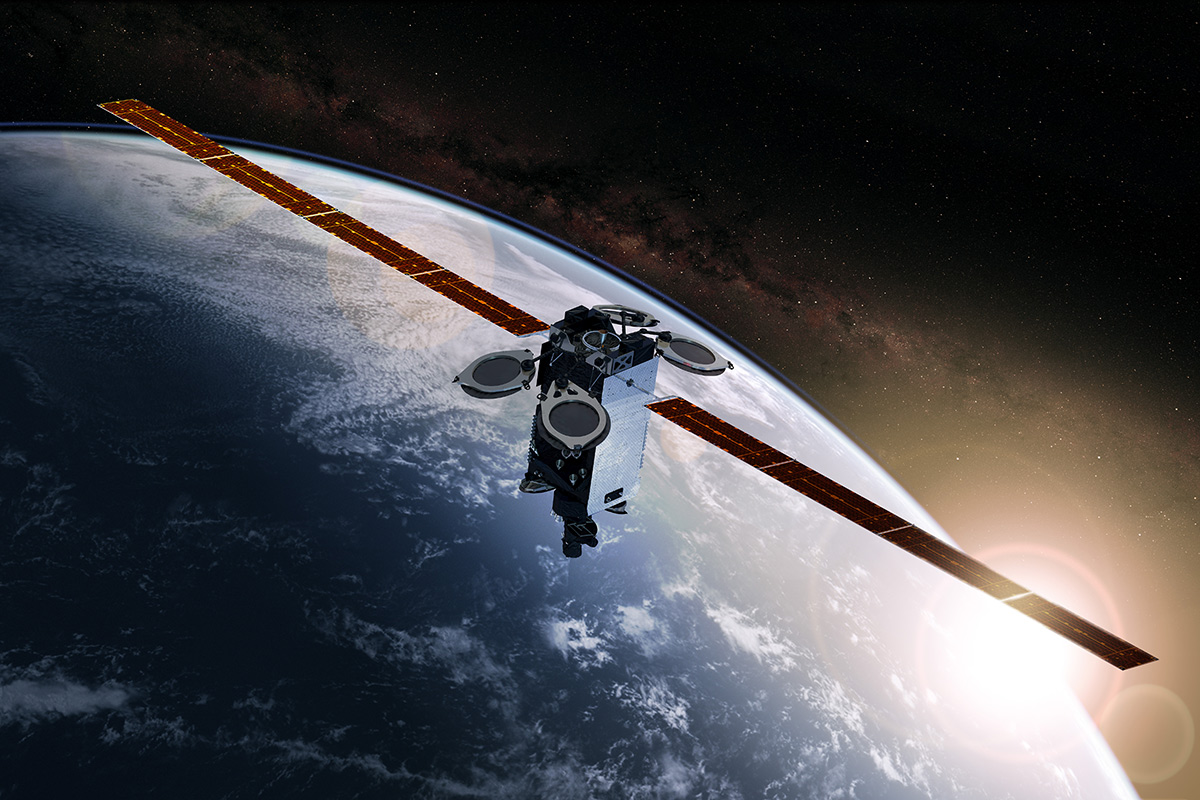

Above: Communications satellites are now an essential piece in the complex jigsaw of military operations but are increasingly being targeted by sophisticated jamming techniques. (Image: Intelsat)

Space defence and military technologies have come a long way since the first spy satellites of the Cold War era. Dropping canisters with film through Earth’s atmosphere for technicians to collect on the ground and develop, these early satellites revealed the secrets of the USSR’s missile testing programmes in a way unthinkable before.

Today, hundreds of satellites take pictures of every spot on the planet every day. Before Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, commercial satellite operators such as Maxar and Planet had been sounding alarm bells about the build-up of troops and military equipment along its borders.

When the first tanks crossed over, the satellites watched them. Since then, conflict has unfolded in front of the world’s eyes nearly in real time thanks to those spaceborne witnesses.

Earth observation constellations are not the only space technology that has provided an indispensable helping hand in Ukraine’s struggle. After Russia took down Ukraine’s internet and cellular networks, SpaceX shipped thousands of Starlink terminals to the besieged country to keep its troops connected.

Help from above

Speaking at the Defence in Space conference in London on 11 September, Oleksandr Danylyuk, chairman at the Centre for Defence Reforms, a Ukrainian think tank, admitted that without access to cutting-edge Western space services, the remarkable morale of the country would not have sufficed against a numerically superior enemy.

‘From the very beginning, it was absolutely clear that Russia is bigger, has more human resources and a much more capable defence industry,’ he said. ‘We were completely outnumbered and outgunned. But mostly because of the support provided by commercial [space] companies, we had a much better understanding about what was going on in our territory and even our satellite communications were better.’

The Ukrainian example demonstrates how crucial space technologies have become for 21st century warfighting and defence. Switch off space and you might as well switch off all your capability.

Monitoring enemy positions and progress, sending and receiving information anywhere through encrypted communication links, providing navigation for warfighters, weapon systems and more – all this is done via a multitude of satellites orbiting hundreds and thousands of miles above the planet.

Above: 2023 saw over 200 successful orbital launches, adding to the thousands of satellites already in space. (Photo: USSF)

‘Whether they know it or not, any military commander right now is absolutely, wholly, completely and utterly dependent on space,’ Nik Smith, regional director UK and Europe for Lockheed Martin Space, told Shephard. ‘We have, in the Western world, created militaries and trained and equipped them with the understanding that they are going to have almost ubiquitous and uncontested access to space services.’

Clayton Swope, a senior fellow in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), described space technologies as ‘the glue’ that enables all kinds of forces to coordinate their actions.

‘If you take that away, if you take away something like satellite communications or positioning, navigation and timing from space, you go back many decades,’ he told Shephard. ‘You go back, for the United States, as far as Vietnam. We are talking about pulling out maps and compasses.’

Cyber siege

Western militaries’ dependence on space assets is no secret to potential adversaries. According to Rory Welch, VP of global government and satellite services at satellite communications provider Intelsat, satellite systems used in the war in Ukraine are experiencing ‘an order of magnitude’ more jamming, spoofing and other cyber-attacks than they did in any other conflict before.

‘Most of the other conflicts were fairly benign with respect to electronic warfare,’ Welch said at the Defence in Space conference in London.

For SpaceX, running Starlink services in Ukraine has been a crash course in cyber resiliency and a test of ingenuity. Kevin Seybert, the company’s government sales manager, also speaking at the conference, described the challenges it faced keeping terminals running when access to global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) such as the US GPS was blocked by jamming.

‘It was really the first time that we had seen our terminals operating in a GNSS-denied environment,’ Seybert said. ‘With many terminals active all at the same time and seeing very similar kind of impacts, we realised that the GNSS-denied environment was causing performance issues. It was causing issues with terminals being able to enter the network and maintain our connection to the network.’

SpaceX swiftly rolled out new software that enabled Starlink satellites to establish their position using their own Ku-band signal, transmitted through the constellation’s network of 100Gbps optical inter-satellite links. These enable each satellite of the 6,000-plus constellation to be in constant contact with a ground station even when not in its direct view.

Resilience required

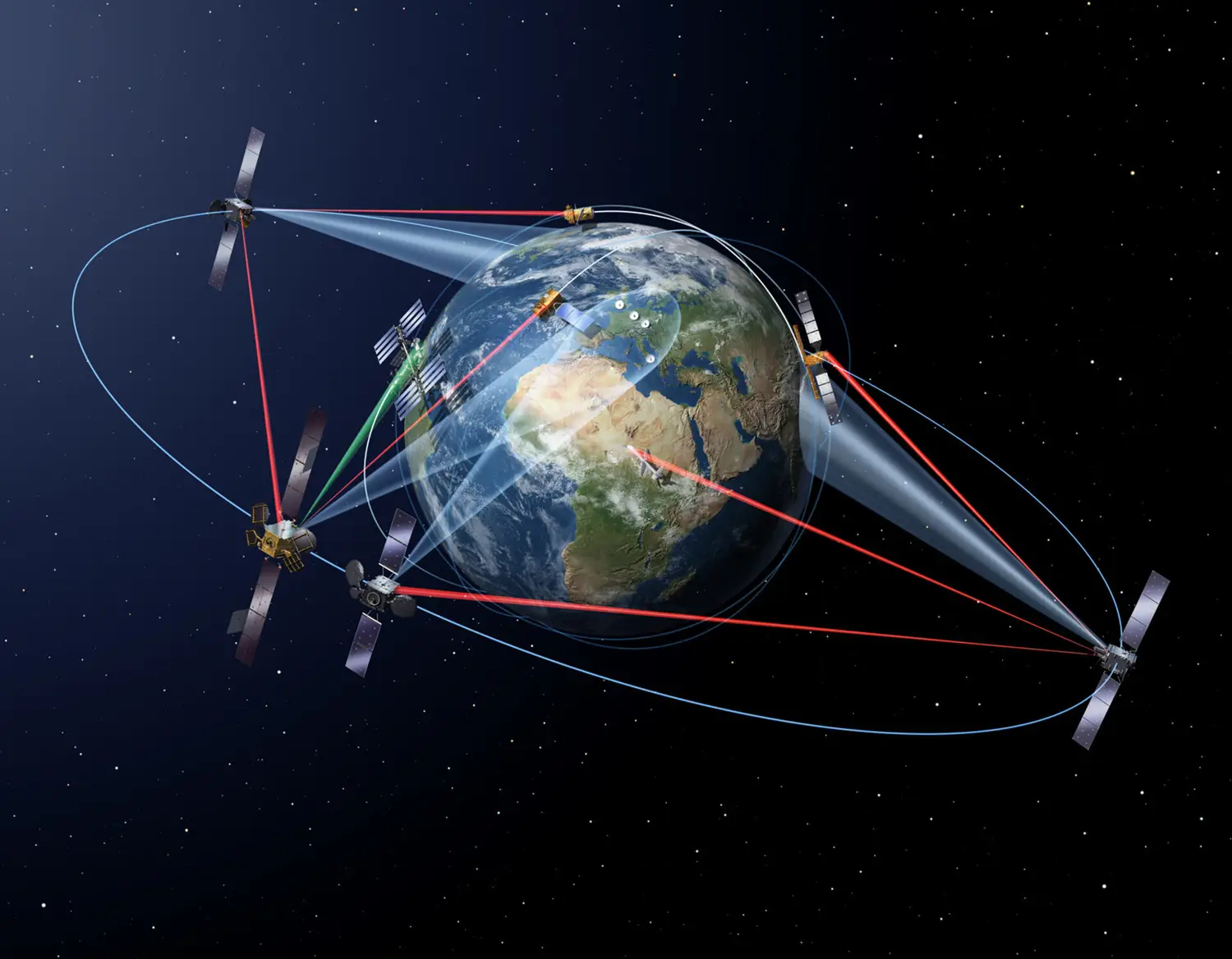

These inter-satellite links are one of the hot technologies of today that promise to increase resiliency of space systems against attacks, according to Juliana Suess, space security research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK think tank.

‘Being able to communicate amongst different satellites to potentially circumvent a ground station that's compromised, or satellites, these are the kind of resilience measures that are really changing the game at the moment,’ she told Shephard.

Above: Using optical Inter-satellite links creates a more resilient network across a constellation and its ground stations. (Image: ESA)

Russia’s attacks on GPS signals in Ukraine have affected the use of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) technology that turns unguided bombs into precision guided weapons, the HIMARS mobile artillery rocket system and the Excalibur guided shells, according to Suess.

Soft-kill space weapons based on electronic warfare tools such as jamming and cyber-attacks are currently the most widely utilised component of the anti-space arsenal being used by adversaries against Western forces and their allies.

But hard-kill systems such as anti-satellite missiles (ASAT) have previously been tested as well. Countries including China, India and Russia have shown off this type of missile technology in debris-creating tests targeting their own spacecraft. Destroying someone else’s satellite, however, is a ‘red line that hasn't been crossed’ yet, said Suess.

‘No one's ever used an ASAT against another state’s satellite,’ she said. ‘For the moment, at least, we've only seen electromagnetic interference and cyber-attacks against other satellites, which I think is likely what we'll be seeing for quite some time.’

Strike capabilities

The increasing dependence of countries like China on space technologies suggests a reluctance to use weapons that would litter swathes of near-Earth space with debris, making the environment unsafe for virtually everyone, Suess thinks.

But Lockheed Martin’s Smith warns that countries with more rudimentary space technologies might consider such a strike. ‘There is always a risk that we end up assuming they would see that impact the same way that we would,’ he said. ‘It’s a dangerous assumption because if you look at, for example North Korea, they might be willing to do it because they are not as dependent on space as we are.’

Even waning space power Russia might be willing to accept such a risk. In fact, in April this year, Moscow vetoed a resolution at the UN Security Council urging member states to prevent deployment of nuclear weapons in space. In May, the US Department of Defense said Russia was developing an orbital nuclear bomb.

‘A nuclear detonation in space is a real threat,’ Smith said. ‘If you detonate a nuclear weapon in space, it pretty much takes out the whole low Earth orbit for years. You pump it full of radiation and the satellites can’t survive because they were not built for that.’

Some 10,000 satellites currently orbit in this congested region – including most Earth-observing satellites and the communication constellations run by SpaceX and OneWeb.

Above: China’s own ambitions in space mean it is unlikely to risk using weapons that cause widespread damage in low Earth orbit, but other actors may not be so reticent. (Photo: CASC)

‘If everyone was equally reliant on space, it would probably be more stable,’ said Swope. ‘With Russia, because their reliance on space has probably decreased, they might use it as a lever to pull on that would have less of an impact on their own ability to conduct military operations but a preponderance to impact countries like the US.’

Smith thinks that the best way to prevent such a strike is to make sure the enemy understands that Western allies have other assets in space to switch to if needed.

‘What you do is you make sure that you have redundancy in other orbits and you think about how actually you can operate beyond low Earth orbit,’ he said. ‘If they see that we would be able to replenish quickly, it changes their cost calculus. They might see it as not worth doing because we would be able to respond.’

Large constellations are by design more resilient than the old-school monolithic satellites developed by space agencies in the past – it is no longer enough to take down one spacecraft to blind the enemy.

Not putting ‘all your eggs into one orbit’ but distributing them across a range of altitudes will result in systems that will keep running even after an ASAT strike or a nuclear explosion in low orbit, said Suess.

In medium Earth orbit at altitudes between 2,000 and 35,000km or in geostationary orbit at 36,000km, satellites will survive a space debris disaster in LEO. A system of multiple interoperable constellations will mean a back-up is available in case of a devastating cyber-attack.

Regardless of the ultimate outcome of the Ukraine conflict, the threats are here to stay. Speaking at the Defence in Space, Justin Keller, director of advanced communications at Lockheed Martin Space said that available intelligence suggests that the problem ‘is only getting worse’.

‘There is no good news,’ he said, pointing to the fast progress China has made in developing new jamming and other space warfare technologies. ‘They are outthinking us in many ways,’ he concluded.

Clearly, Western nations need to invest in ways of staying in this particular space race or face some extremely negative consequences back on Earth.